F*luxx Galerie I Soheila Sokhanvari (English)

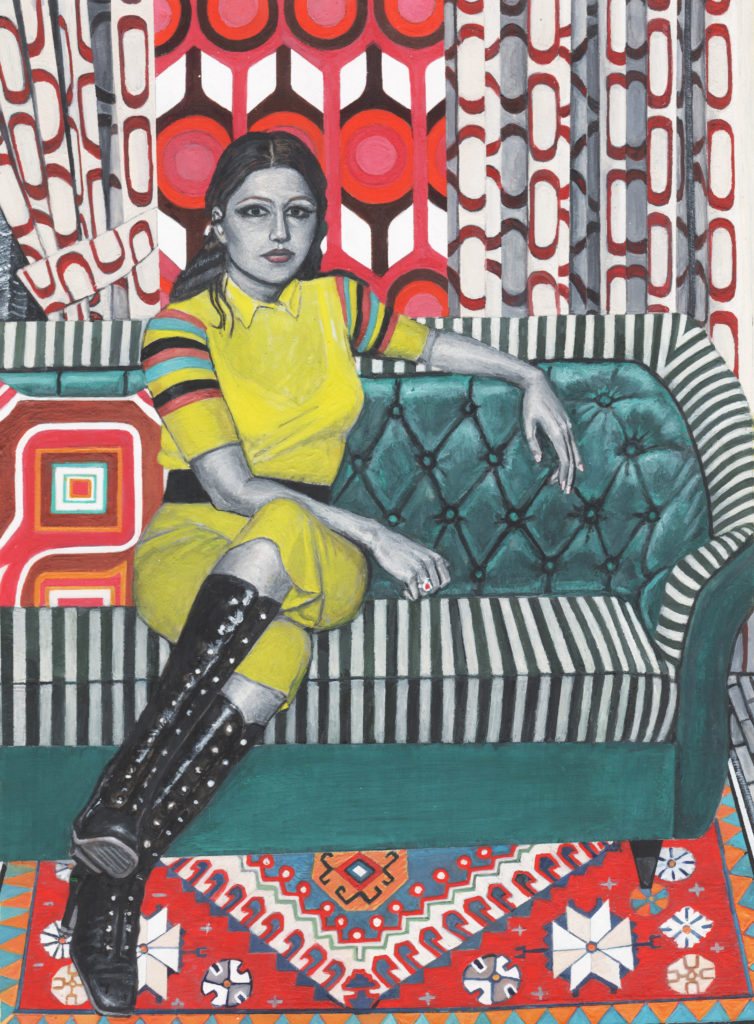

The art of the Iranian-born, London-based artist Soheila Sokhanvari is in the tradition of Persian miniature painting. he women she paints, richly decorated and on parchment, are the heroines of her childhood. With her multidimensional installation art, Soheila Sokhanvari puts the women artists of the past in the spotlight, which they were denied throughout their lives.

We spoke to the artist while her exhibition “Rebel Rebel” was shown at ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark this year.

Here you find the German version of the interview.

Why did you choose women as your subject?

Soheila Sokhanvari: These women were like icons in my childhood. They were singers, actresses, dancers, or poets, and they sacrificed a lot to pursue their careers. Defined as cheap women or whores, they were not considered suitable to marry into respectable families. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, they faced threats from the government, as well as from their own families. Some were imprisoned, and all their possessions were confiscated, as in the case of Kobra Saeedi.

What happened to her?

Kobra Saeedi was an amazing, creative, clever and very liberal artist. After the revolution, she was forced, like other women, to sign a letter of repentance for her career. They were not allowed to perform in public spaces anymore. Khomeini decreed that women had to wear hijabs. On International Women’s Day, they protested the hijab. Kobra Saeedi went into the streets with her camera and made a documentary. Because she was famous, she was arrested. They confiscated her property, froze her bank account, and subjected her to electroshock treatment. Later, she was released into the streets of Tehran and became homeless. It was not until 2015 that she was given a shack, which charitable people found for her.

That really is too sad …

Yes, it is. When I was researching these women on the internet, there was only a small amount of information available because the government had removed it from the cultural history of Iran. I felt compelled to bring their stories back to the public platform. I wanted to honor what they had achieved.

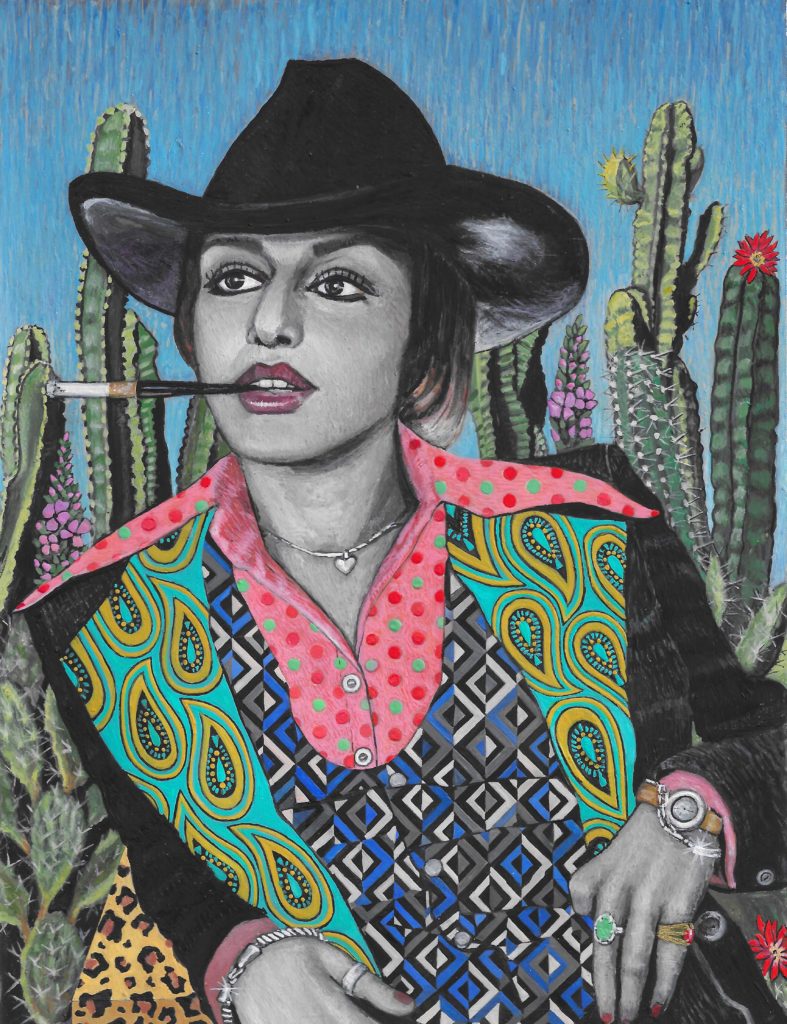

A lot of the images I paint are based on photographs I find online. There were only three images of Kobra Saeedi. Although they were passport sized, I couldn’t take my eyes off one photograph which shows her face. I just sat there and looked at it for two weeks. Eventually, this photograph spoke to me: She took a drag of a cigarette. I had that moment in my mind. I posed in that position, my husband took a photograph of me and I lent literally her my body in my painting of her. This is why I feel so connected to the picture.

When you say you lent her your body and you feel very connected, why?

As Iranian people, we are exiles. I feel I have lost my country; I have lost my family; I have lost my language and my background. The culture in Iran changes behind my back. It is a loss of everything. Maybe the connection between her and me is that she was an unappreciated woman.

You feel unappreciated in what sense?

I don’t know if I feel unappreciated. But as an Iranian woman, I don’t feel as visible as Western women. There is a sort of othering that has made me fight all my life. I was born in Iran, where as a woman, you are a second-class citizen. You don’t have the same legal rights as men.

How old were you when you left Iran?

I left my family in 1978, a year before the revolution started. I was 14 when I came to England with my 17-year-old brother. We were separated soon after as we went to different schools and different cities.

Why did your parents send you overseas?

My family wanted me to have a good education. During the Pahlavi era, it was fashionable to send you abroad if a family could afford it. Because when you returned, you had a better chance of getting a higher position in your job and being paid more. My mom insisted that I become a doctor, a lawyer, or an engineer. Becoming an artist was not an option. I studied biochemistry and graduated as a biochemist in 1996. I worked for 18 years as a research scientist.

Then I took a leap of faith and became an artist, which meant going from a regular income to no income, to a negative income because I had to pay the university. It was madness, but I had to become an artist—it was a matter of life and death for me.

Why this urgency?

I had a bike accident during a charity bike ride for the British Heart Foundation. I went down a hill and collided with two bikes in front of me. I flipped over and landed on my neck. For about four hours, while I was in the hospital getting X-rays, I didn’t know if I would be able to walk again. During that time, I told myself that if I recovered, I would follow my dream of becoming an artist. I didn’t want to lie on my deathbed and wish I had done something differently. I wanted to pursue my dream while I was still active, healthy, and young.

That was a brave decision.

No. That has nothing to do with bravery. When it comes to a matter of life and death, I don’t think it’s bravery. It is very practical. What did I have to lose besides my dreams? I think it is better to fail than to have regrets.

Returning to your exhibition and its setup and design: When entering the room, it feels like stepping into another world. It is dimly lit, with the paintings illuminated by spotlights, the walls adorned with oriental patterns, and the space filled with Iranian music. It provides a complete immersion into your art.

I felt that I had to create a temple for these women. To me, they are goddesses to be worshipped. Iran has always been Islamic, and I wanted to create an Islamic-inspired temple for them, with theatrical spotlights on the pictures so that viewers can become intimate with the artwork. The small size of the paintings means you must get very close to appreciate them fully.

My intention was to immerse the viewer in Persian culture, to bring them into the space, to let them listen to the music, and to hear Iranian women singing, as they are not allowed to sing in public anymore. I wanted to give their voices back and create a real sense of what it was like to live in Iran and be part of that culture. It’s about honoring them, giving them a space they might never have had, and challenging conservative views that have historically suppressed women’s autonomy and visibility.

The setting reminds me of a church or a mosque.

That’s my intention. If you walk into a mosque, everything is patterned. The reason for that is: Grand mosques want to create a beautiful space where the individual loses their sense of self to contemplate God. This sense of delirium in presence of overwhelming beauty is described by Elaine Scarry in “On Beauty and Being Just” as a “opiated adjacency” that makes us experience delirium and have an out of body experience.

Traditional references on the one hand and modern on the others. Your artworks are named after pop songs. Why?

Historically, Persian miniatures were named after the poems or stories they illustrated. I see my work in that tradition and place it into a modern context by naming my paintings after pop songs, which I consider to be modern poetry. Songs by artists like Bob Dylan or David Bowie are rich in meaning and emotion, and they complement the themes of my work. When you walk into the exhibition titled “Rebel, Rebel” and have Bowie’s song “Hot tramp, I love you so” in your head, it adds another layer of meaning to the pictures. These women are rebels who we should love, like Mahsa Amini. They are all symbols of rebellion.

Did the violent death of Mahsa Amini during the protests in Tehran in 2022 impact your work?

The protests provided context for my art. Up until then, many people saw my work as beautiful and fantastically painted, but they either did not know about these women or did not understand how much Iranian women have been fighting for their freedom. The protests weren’t just about the hijab; they were about the broader issue of women’s autonomy and their legal rights in Iran.

My paintings offer an alternative image of Iranian women to Western cultures. For a long time, Iranian women were depicted in media and art as wearing hijabs, with anti-American slogans, raising their fists and shouting, “Death to America.” By stereotyping Iranian people and turning them into ‚others,‘ Western cultures have made us ashamed of being Iranian. We, as Iranian women, are as creative, witty, sexy, and sassy as any women in the world. By turning people into ‚others,‘ it becomes easier to impose sanctions and political antagonism against them.

I aim to present a different narrative of Iranian women, showcasing their creativity, strength, and individuality. By moving beyond stereotypes, I want to demonstrate that Iranian women are as complex and nuanced as women anywhere else in the world.

How do you balance the beauty and the sadness in your storytelling?

It’s about giving a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down. I use beauty to create a sense of closure to the sadness, making the viewer’s experience more palatable and emotionally resonant.

Is there any question I didn’t ask that would be important for you to answer?

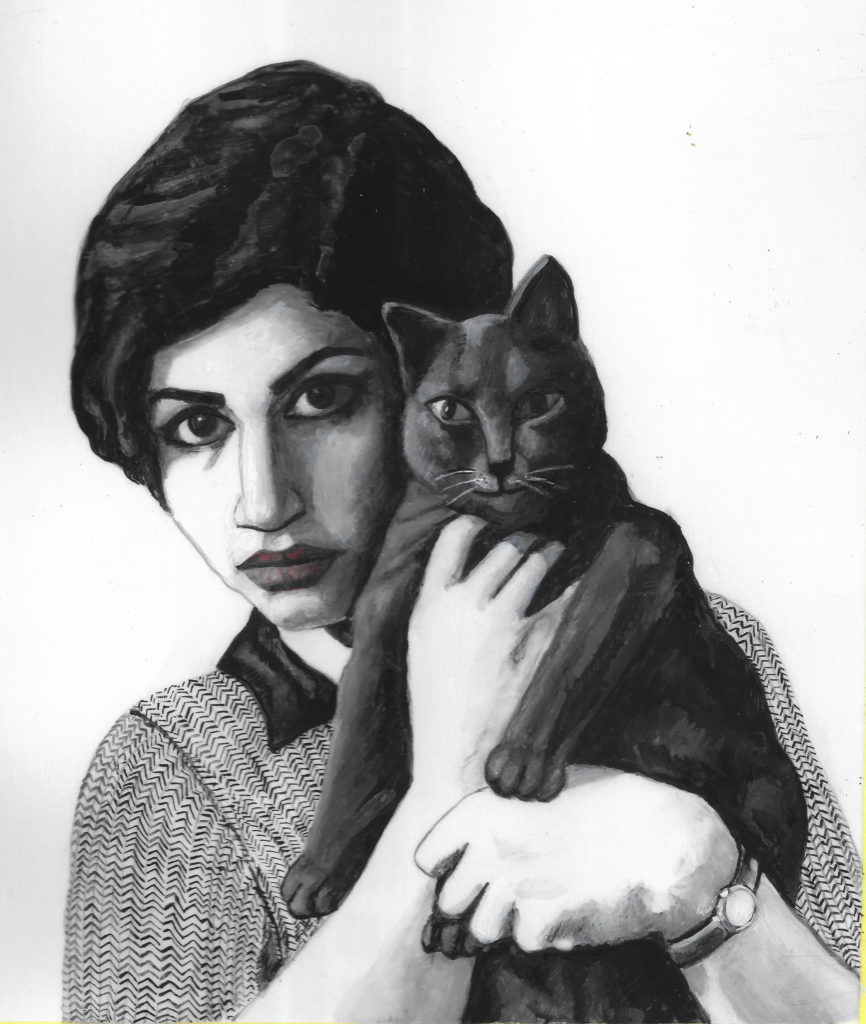

In the beginning, you asked me which artists I really wish to mention. One of my favorite paintings is of a woman holding a cat. It depicts the feminist poet and filmmaker Forugh Farrokhzad, who died in a car accident in 1967 at the age of 32. The painting is named after her poem „Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season,” which I would like to read to you.

Her work resonates with me deeply. Women in Iran today are desperate for freedom – what can I do as an artist? To me, that says everything, because my hands feel like concrete. I feel it is a time when you can connect through history, through words, through your culture, to see something resonate with you through the words of someone who found these words many years ago. Farrokhzad was a wonderful feminist who wrote about her sexual freedom, had relationships, and lived authentically, despite being judged harshly. It’s a poignant reminder of the double standards that still exist.

Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season

And this is I

A woman alone

At the threshold of a cold season

At the beginning of understanding

The polluted existence of the earth

And the simple and sad pessimism of the sky

And the incapacity of these concrete hands

(...)

Forugh Farrokhzad (1934 - 1964)

Soheila Sokhanvari is an Iranian-born artist whose multidisciplinary work weaves layers of political histories with bizarre, mysterious and often humorous narratives that she leaves open to viewers to complete. Soheila Sokhanvari received her BA in Art History and Fine Arts from Anglia Ruskin University in 2005, a postgraduate diploma in Fine Art from Chelsea College of Art and Design in 2006 and an MFA from Goldsmiths College in 2011. She has has exhibited extensively throughout Europe and the Middle East. In 2027/28, the Frieder Burda Museum in Baden-Baden will dedicate the world’s first major retrospective to the artist. Soheila Sokhanvari is represented by Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery London Berlin. Learn more about the artist on her website.

© Soheila Sokhanvari at ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, 2024, Mads Smidstrup

The curator of our F*luxx Galerie is Anette Frisch, who also conducted the interview.